As a good millennial, I’ve read more self-help books than I’d care to admit.

My productivity system runs on David Allen’s Getting Things Done. Marie Kondo tells me how to fold my laundry. When adopting a new routine, I review my copy of Atomic Habits.

It’s easy to make fun of self-help. Self-help is the kind of low-brow thing you might guiltily flip through at the airport bookstore. However, to really understand the human condition, you should study Dostoyevsky.

Such snobbery misses the point. Most problems we face aren’t that unique. The challenges we confront have already been solved by thousands of other humans before us. They’ve even written down the cheat codes. Why throw that away?

Still, something has always bothered me about self-help: Too often, self-help downplays the existence of hard trade-offs.

(To be clear, self-help contains a lot of obvious fraud and hucksterism—manifesting wealth through moon rituals, etc. That’s bad, but I want to point to something more subtle.)

Imagine you’ve picked up a time-management book—not unlike Getting Things Done—because you’re struggling to juggle your work and family. There’s just not enough time for both!

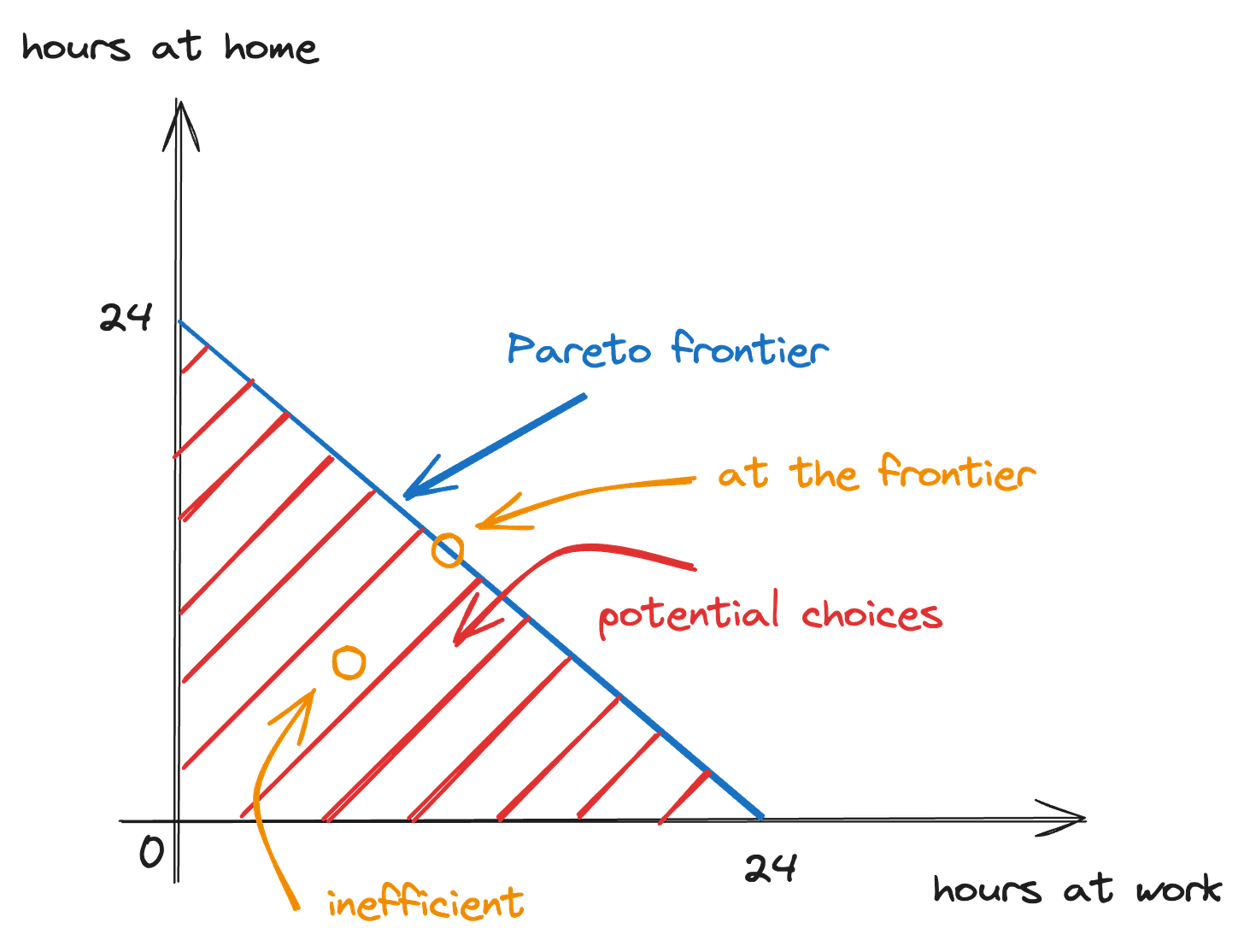

Let’s model this. Effectively, you have a choice of how much time to spend at work vs with your family. We can depict that choice in a graph:

There are 24 hours in the day. You can either spend them at work (x-axis) or at home (y-axis; think of “hours at home” as a catch-all for all kinds of non-work stuff). The red-shaded area represents all potential choices.

However, there’s a fundamental limit to what is physically possible. That limit is called the Pareto frontier:

The Pareto frontier traces out all potential choices that are efficient (or non-wasteful). Since an hour extra at work is time you can’t spend with your family, the Pareto frontier slopes downward.

There are two logical possibilities. Maybe you are not at the Pareto frontier, as illustrated by the orange point below:

In this case, you can increase both “hours at work” and “hours at home.” Maybe you’re wasting time doomscrolling on social media, or you can be more productive by adopting those productivity hacks in Getting Things Done. By eliminating waste, you can have more of everything.

However, there’s a limit to how far you can push this. At some point, you’re at the Pareto frontier:

You’re now facing a hard trade-off: You can only spend more time with your family at a cost to work.

That’s what I mean by the title of this post. Most of us start somewhere around that orange point. Here, optimization helps, and best practices can get you more of everything. Eventually, though, you’ll hit the Pareto frontier. Sooner or later, there’s always a trade-off.

While I’ve used a time-management example, the point is more general:

Pursuing your passion project probably means less financial stability;

Embracing a nomadic lifestyle probably means fewer deep social ties;

Achieving Zen-like calm probably means letting go of the need for flawless results.

The Pareto frontier for these choices is less obvious and linear, but it’s still there, somewhere.

To be fair, some self-help books address life’s trade-offs directly. Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks tackles these with refreshing honesty:

Nobody in the history of humanity has ever achieved “work-life balance”, whatever that might be, and you certainly won’t get there by copying “six things successful people do before 7 a.m.”. The day will never arrive when you finally have everything under control—when the flood of emails has been contained; when your to-do lists have stopped getting longer; when you’re meeting all your obligations at work and in your home life; when nobody’s angry with you for missing a deadline or dropping the ball; and when the fully optimised person you’ve become can turn, at long last, to the things life is really supposed to be about.

Life is full of hard choices, and no amount of clever hacks can change that. But maybe that’s okay. Maybe self-help is less about eliminating trade-offs and more about learning from those who have already traveled the same path, grappling with the same harsh realities we all face.

As long as there’s no manifestation through moon rituals, that doesn’t seem so bad.

I think most of us initially don’t have a clear idea on how far away we are from the Pareto frontier. That’s why reading the first one or two self-help books seems to bring so much value. It enables us to make huge steps towards that limit. However, any additional book brings diminishing returns. Said that, I still enjoy reading books that can help me improve my life. Although more recently I’ve been drifting from self-help towards philosophy.