Is capitalism making you lonely?

There's a loneliness epidemic. Is capitalism to blame? Here's what the data says.

I. Loneliness & capitalism

There’s a loneliness epidemic worldwide:

Is capitalism to blame?1

A long tradition of thinkers would say “yes.” In his famous theory of alienation, Karl Marx argued that capitalism estranges people from others:

“An immediate consequence of the fact that man is estranged from the product of his labor, from his life activity, from his species-being, is the estrangement of man from man. When man confronts himself, he confronts the other man. What applies to a man’s relation to his work, to the product of his labor and to himself, also holds of a man’s relation to the other man, and to the other man’s labor and object of labor.” (emphasis mine)

If 19th-century philosophy isn’t your cup of tea (I feel you), check out “How Capitalism Causes Loneliness” by the YouTuber Second Thought.

I’ll admit: I’m more pro-capitalism than many folks. Partially, that’s because of personal experience. I grew up in a post-Soviet country, and while I haven’t personally experienced communism, I know enough to be grateful to live in a free, capitalist society. As a result, I’m naturally suspicious of claims that “capitalism causes [insert some bad thing].”

That said, there are plausible arguments why capitalism may increase loneliness:

Capitalism could demand long working hours, leaving less time for friends and family;

By thriving on competition, capitalism may promote individualism over communal values;

Capitalism can encourage buying things instead of building relationships.

However, there are convincing counter-arguments, too:

With its focus on innovation, capitalism has reduced work hours;

Capitalism creates jobs and provides services that are needed by the community;

Capitalism requires building things other people want.

We could argue until the cows come home and not make any progress.

At the end of the day, whether or not capitalism leads to more loneliness is an empirical question. We can’t answer it by armchair philosophizing or appealing to what Karl Marx—or Adam Smith, for that matter—wrote hundreds of years ago.

We need evidence.

II. Data

Let’s gather some data and see what we find.2

I use two main data sources:

To quantify capitalism, I employ the Index of Economic Freedom from The Heritage Foundation. That’s a commonly used metric of how “capitalist” a society is;

To measure loneliness, I leverage the State of Social Connections study conducted by Gallup and Meta in 2022. The main measure of loneliness is the percentage of the population that reports feeling “very or fairly lonely” when asked, “In general, how lonely do you feel?”.

Here are the resources to replicate my work or dive into the underlying data:

III. Results

The dataset covers 133 countries, as shown in the map below:3

III.A. Main finding

Before looking at the data, take a guess: What do you think is the correlation between loneliness and capitalism? Do you think it’s positive, negative, or zero? How strong do you think the relationship is?

Take a moment to make your prediction before reading on.

Do not scroll just yet, please.

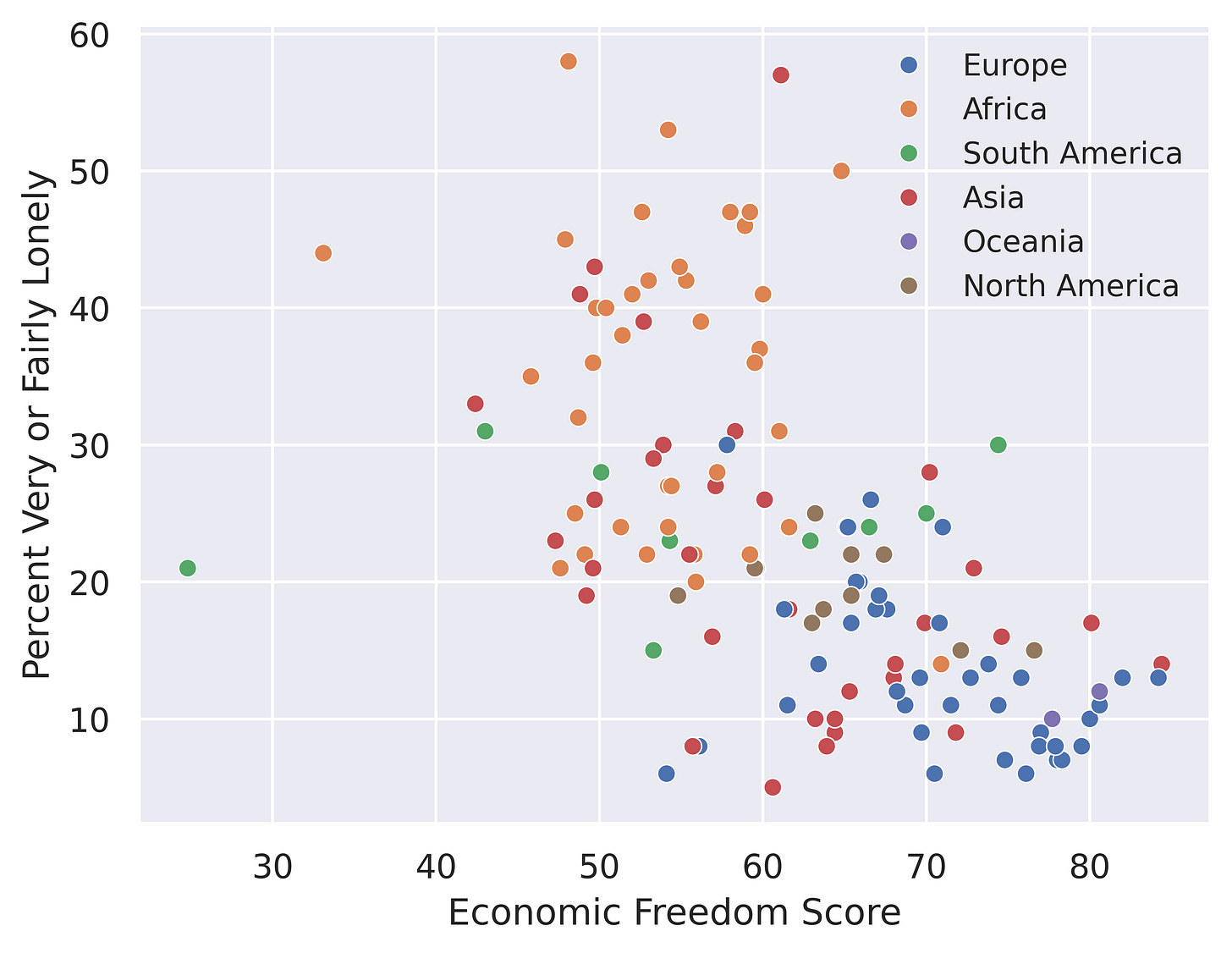

Here’s loneliness plotted against the economic freedom score—our measure of capitalism:

I have consciously not drawn the line of best fit here; it’s just the raw data. There’s some spread, especially for lower economic freedom scores, but overall it looks like a negative relationship.

Next, I add the estimated least-squares fit and reveal the correlation level:

That’s a negative correlation of -0.57. Economic freedom and loneliness are moderately negatively correlated.

Is that what you predicted?

Personally, I expected to find little relationship between capitalism and loneliness. I would have guessed that the major drivers of loneliness are social and psychological, not economic. Once I saw the negative relationship, I thought it would disappear after some minor changes in the analysis. However, as we will see, the correlation is fairly robust.

According to these estimates, a ten-point increase4 in the economic freedom score is associated with a 6.5 percentage-point decrease in loneliness (95% confidence interval: [4.8, 8.3]). In standard deviation terms, that’s roughly a 0.5 standard deviation decline, a moderate effect size.

III.B. Is this correlation robust?

Does this result hold up to scrutiny?

For the first robustness check, I replicate the analysis with an alternative metric of loneliness. I now use a measure of “social connectedness” (i.e., inverse of loneliness). As expected, there’s a positive relationship between economic freedom and social connectedness:

Next, you may worry about omitted-variable bias. One specific concern is that loneliness varies over the lifecycle. Previous research has found that loneliness follows a U-shaped pattern, with young people and the elderly being more lonely than those in middle age.

To test for this possibility, I control for the percentage of the population aged 25–64 years (i.e., the middle of the age distribution):

While the correlation is roughly halved, it remains negative and statistically significant: A ten-point increase in economic freedom corresponds to a 3.7 percentage point reduction in loneliness (95% confidence interval: [1.8, 5.6]).

In the Colab notebook, I report several additional tests. For example, the negative relationship between economic freedom and loneliness persists after controlling for overall freedom, as measured by the Freedom House index. There’s still a negative relationship when accounting for Hofstede’s measure of individualism.5

III.C. Panel-data evidence

The evidence so far is all cross-sectional. While this is more informative than armchair philosophy, such evidence is still limited. There could be omitted variables correlated with both capitalism and loneliness. An example, as we saw above, is age structure. Other confounds could include geography or culture. While we can try controlling for these variables, it’s impossible to account for every imaginable confound.

Thankfully, there’s one additional trick. We can ask whether countries that become more capitalist become more lonely. Now we’re making a comparison across time, not just across countries.

For that, I use OECD data to measure social support in 2016. First, again looking at a point in time, there’s a positive relationship between economic freedom and the OECD connectedness metric:

This finding is reassuring: We get the same results using the economic freedom score from a different year, and a measure of social connectedness from an unrelated source.

Now, let’s combine the two datasets:

For each country in the OECD subsample, calculate its “loneliness rank” in 2016;

Then, calculate the “loneliness rank” in 2022 using Gallup data;

Follow the same procedure to calculate the “economic freedom rank” for countries in 2016 and 2022;

Correlate changes in loneliness and economic freedom ranks.

Note the key change: We’re comparing changes over time. Fixed characteristics in countries, like geography or culture, that stay roughly constant between 2016 and 2022 won’t affect the correlation. This makes the evidence much more credible.

The results are again good news for capitalism:

This correlation is statistically significant: Moving up by 1 place in the economic freedom ranking improves the loneliness ranking by around 0.60 places (95% confidence interval: [0.20, 1.02]).

To be clear, this “change in ranks” analysis isn’t super strong evidence. We’re talking about a sample of 41 countries and a correlation of -0.36. However, when taken together with the evidence previously, it paints a consistent picture: Capitalism doesn’t appear to cause loneliness.

IV. Related research

My results align with a broader body of research suggesting that economic freedom is associated with reduced loneliness and improved well-being.

In a Reason article, Johan Norberg cites a study by Caspian Rehbinder who found that

For every point a country gains on the Cato Institute and Fraser Institute's 10-point scale for personal and economic freedom—in effect, a measure of a country's classical liberalism—loneliness is on average six percentage points lower.

After much googling, I’m unable to find the study by Rehbinder. However, my point estimates are remarkably similar. My preferred estimate—from the regression that controls for the age structure—is that an equivalently-sized improvement in economic freedom reduces loneliness by 3.7 percentage points.

A recent study by Boris Nikolaev and Daniel Bennet also found that economic freedom reduces loneliness (EFW stands for the “Economic Freedom of the World” index):

Differently from me, these authors used individual-level data.

There’s also an established literature on the relationship between economic freedom and subjective well-being. That literature generally finds a moderate positive relationship. For example, this study by Kai Gehring reports a correlation of 0.55 between life satisfaction and economic freedom (see Table 1).

V. Conclusion

Many people are worried about rising loneliness. Is capitalism the culprit?

The data tells a different story: Capitalism, if anything, reduces loneliness.

My analysis is silent on how capitalism does that, though I’d bet it’s mostly via higher GDP. That is: Higher economic freedom → higher material well-being → less loneliness.

Economic freedom is indeed strongly correlated with GDP per capita:

Money can buy many things, including time. If you live in a rich country, you may have the luxury of working part-time to spend more time with the family. That isn’t an option if you’re struggling to make ends meet.

Now, I’m venturing into speculative territory. However, I worry that in rich countries, we underestimate the importance of material well-being. Sure, GDP doesn’t account for inequality, health, or hours worked. But once you do the work, it turns out that GDP per capita is a pretty great metric for welfare.

The danger of underestimating the importance of money is that you risk biting the hand that feeds you. Improving social connections is tough, but destroying material well-being is all too easy. History is full of countries that squandered their wealth.

The arguments for “capitalism causes loneliness” do sound plausible. Marx had some reasonable points. Unfortunately, when you look at the data, they don’t hold up.

None of that is to say that capitalism is perfect, or that loneliness isn’t a real problem. However, we need to stay grounded in the data.

And while we’re at it, maybe we should show capitalism some love. Capitalism has generated incredible material wealth. It may even have made us less lonely.

There is some debate if there really is an epidemic of loneliness. Check out this article by Esteban Ortiz-Ospina from Our World in Data for more context.

The ideal experiment would involve randomly assigning countries to either a treatment group, where capitalism is increased, or a control group, and then comparing loneliness between the two. This is clearly not feasible, so my analysis relies on observational data. A natural experiment approximating this “ideal” is the division of East and West Germany post-World War II. Post-reunification, people in the formerly socialist East Germany were significantly more lonely (ungated preprint).

That’s roughly a one standard-deviation increase in economic freedom.

Hofstede’s measure is unavailable for many countries in the sample, reducing the sample size to only 65 observations. Consequently, economic freedom is no longer statistically significant (p-value: 0.11).

I recommend checking out this article, which posits that "human beings want much richer social lives than they can maintain under strict market conditions, and much of the reaction against market societies comes from that" https://samzdat.com/2017/06/01/the-meridian-of-her-greatness/

I love how this is written, engaging and thoughtful.