Regulating AI

A map of the terrain

The year is 2030. Months of unemployment stretch before you, as your once-secure job as a senior back-end developer has been destroyed by the latest iteration of Codex. Fabricated news stories infest social media. A viral video circulates, depicting a swarm of rogue drones kidnapping a local influencer, but you can no longer discern fact from fiction.

Such scenarios were once reserved for chilling, dystopian tales. Now, however, these concerns are becoming a reality due to the meteoric rise of AI. As we grapple with these issues, how can we effectively address and mitigate their impact? How should we regulate AI?

This question has now firmly entered the mainstream debate. Last week, The Future of Life Institute published an open letter calling for a moratorium on new AI developments. This message garnered support from figures such as Yoshua Bengio, Elon Musk, and Steve Wozniak. Meanwhile, Italy banned ChatGPT over privacy concerns. Finally, in a controversial Time article, Eliezer Yudkowsky advocated for potential military intervention.

In this post, I will critically examine the arguments for and against regulating AI. My goal is to provide a map of the terrain. I don’t have well-formed personal views and am just as confused as anyone else; the map is still blurry. I may be biased, but I will do my best to make these biases explicit.

Full disclosure: I used ChatGPT heavily to write this post. I subscribe to ChatGPT Premium and use it on a daily basis. Does that color my views? Perhaps.

Why regulate AI?

I’m trained as an economist, and I’ll begin the way economists usually do: By first identifying the core market failure. Boring, I know. We’ll get to the “AI annihilates the universe” stuff soon enough, I promise.

Identifying the core market failure is tricky because different rationales for regulating AI are often lumped together. Take, for example, the open letter from the Future of Life. The letter highlights these key risks:

AI may automate jobs;

AI may spread misinformation;

AI may destroy humanity.

These are all “potential bad things that may happen,” not market failures. That is, these are negative outcomes rather than the underlying root causes. However, to develop sound regulations, we must first pinpoint the root cause. So let’s delve deeper into the underlying market failures for each risk.1

When considering the risk of “AI automating jobs,” the market failure most people have in mind is a negative externality on job creation. For example, if GPT-4 is used to automate legal tasks, many lawyers may lose jobs, increasing unemployment. However, when deciding how much to invest in developing the new iteration of GPT, OpenAI is unlikely to consider the consequences on lawyers’ employment opportunities.

That’s not the end of the story, though. AI can both automate old tasks as well as create new ones. We can already see some of that. For example, being a prompt engineer is a thing now. It's hard to say what the total effect of AI on employment will be. Historically, new technologies have created more jobs than they destroyed. But is this time different?

Let’s think about “AI may spread misinformation” next. It’s not immediately clear that there’s a market failure here. At first, it may seem like it’s in the best financial interest of OpenAI to ensure that ChatGPT does not spawn misinformation. And, indeed, in practice, ChatGPT is really tame, as pointed out by Richard Socher:

However, you could make a negative-externality argument here, too. If a rogue actor comes to OpenAI and says, “Hey, how about I give you $$$, and you tweak your API so that I can create inflammatory content and, like, destroy democracy,” it could be short-term profitable for OpenAI to agree. Or, maybe OpenAI refuses, but a less scrupulous AI company steps in. In general, AI companies are likely to take higher risks than the general public would tolerate.

Consider the following analogy. Think of a prominent oil company like ExxonMobil. ExxonMobil has a strong financial incentive to avoid causing oil spills, such as the notorious Exxon Valdez disaster. However, the company's risk tolerance likely diverges from that of society as a whole. Let's say ExxonMobil is willing to accept an annual risk of x% for an oil spill. I would bet that the general public's risk tolerance would be lower than x%. That’s because the public faces the negative externalities from oil spills, such as environmental degradation and damage to local ecosystems.

There are also concerns about “biased AI” or “unethical AI” that fall into the same broad “AI misinformation” bucket. For example, AI may take a particular stance on a highly-charged political issue or exhibit racism. If AI makes consequential decisions—such as deciding whether or not you qualify for a mortgage—these biases could have deeply harmful effects. Again, AI companies have strong incentives to address these issues, but the incentives may not be perfectly aligned.

This brings us to the final and most alarming concern: “AI may destroy humanity.” (I promised we’d get to this.) In this case, at least two market failures are at play: a coordination failure and a negative risk externality.

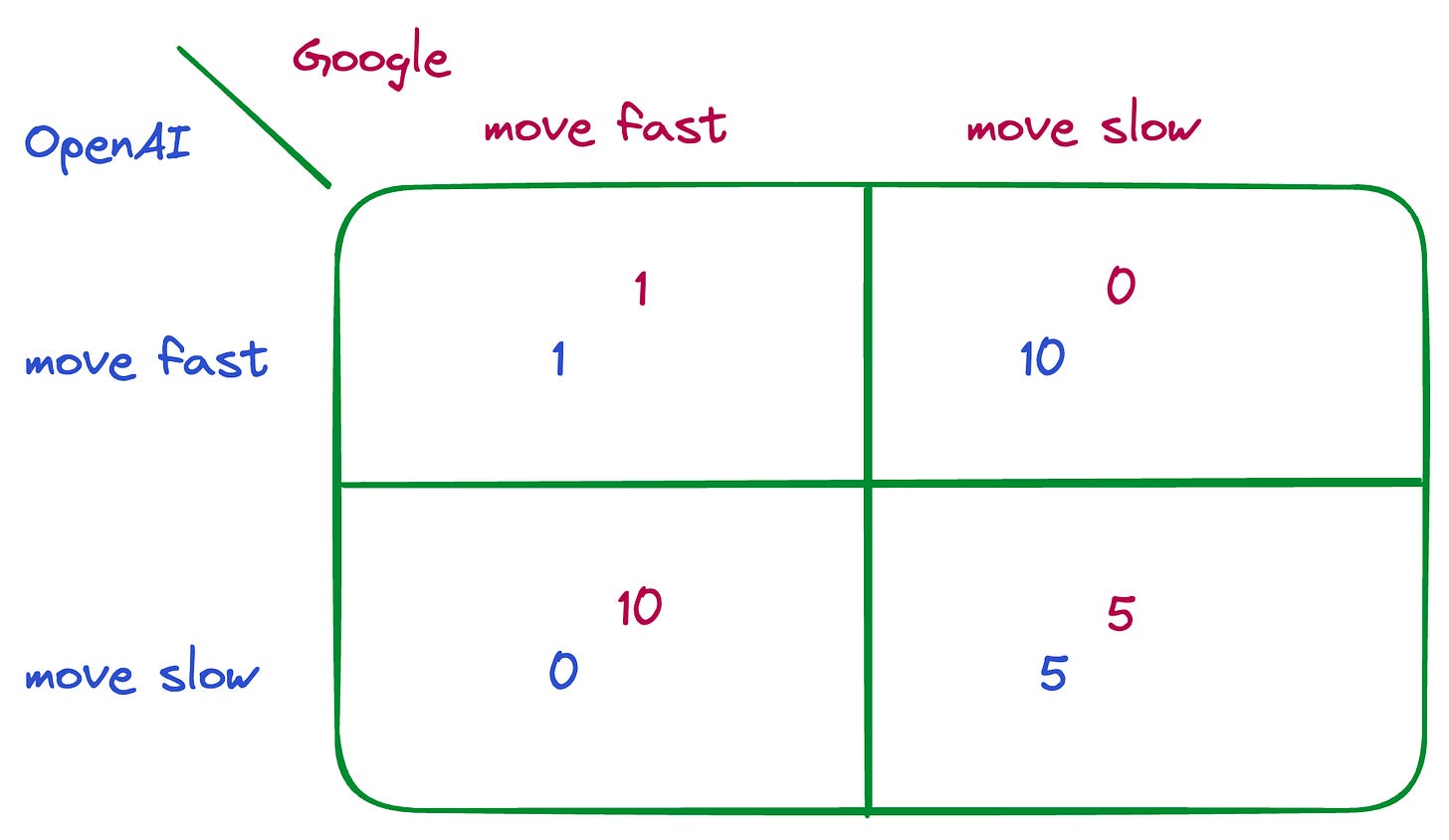

Consider a hypothetical game involving OpenAI and Google (actually, not so hypothetical). Both companies have two options:

Move fast: Develop artificial general intelligence (AGI) as quickly as possible;

Move slow: Attempt to develop AGI gradually, implementing numerous safety measures.

Let’s assume that if both OpenAI & Google play “move slow,” we develop a powerful AGI that benefits humanity immensely (nice) and also does not destroy the universe (also nice). The profits generated from AGI would be shared between OpenAI & Google. However, if Google decides to “move slow,” OpenAI may be tempted to “move fast” to win 100% of the market. Unfortunately, if both Google and OpenAI play “move fast,” we get a competitive arms race; maybe that means no safety guardrails and a high chance of catastrophe.

The payoffs in this AI game may look like this:2

In this game, Nash equilibrium dictates that both OpenAI and Google choose “move fast” even though “move slow” would be mutually beneficial. This outcome embodies the harsh reality of the prisoner’s dilemma.

Next to the coordination failure, a negative risk externality likely exists. Since OpenAI would also be destroyed along with humanity, it has a clear financial incentive to avoid crazy risks. However, as the previous oil spill example illustrates, OpenAI's risk tolerance may differ from society's.

Just as with job creation, though, there are both negative and positive externalities to risk-taking. When we think about innovation, we typically think there’s too little risk-taking, not too much. For example, in an influential paper, Nobel laureate William Nordhaus estimated that innovators only capture about 2 percent of the total social surplus from innovation. That means that the social returns to innovation are much greater than private returns. We can already see this: For example, some companies piggyback on the achievements of OpenAI to build new large-language models more cheaply. That dissipates the rents from innovation and reduces the incentive to innovate and make bets on AI.

How to regulate AI

Let’s now discuss how these three risks (AI may automate jobs; AI may spread misinformation; AI may destroy humanity) may be regulated.

Risk #1: “AI may automate jobs”

“X may automate jobs” is a common concern with any new technology X. I think there are two reasons why the situation here may be different than in the past:

AI may primarily affect high-skilled professions (if you’re a construction worker, you’re probably not very worried about ChatGPT);

AGI can automate literally everything a human can do. What do we, humans, do then?

Adam Ozimek articulated that first point nicely in a recent tweet storm:

The general answer to a tech disruption is well understood: Provide a generous safety net and create ample opportunities to retrain. Of course, we need to work out exactly how “retraining” looks in practice. But, in theory, we have a game plan.

There’s a big difference between AI’s short- and long-term impacts. In the short term, AI will only automate a subset of tasks that a human can do. If history is any guide, our standard policy tools should be sufficient. However, we must be vigilant, as without an active policy, social cohesion and income equality will face serious challenges.

However, once we have AGI, “this time is different” really does apply. At that point, anything a human can do, AGI will be able to do as well. If all goes well, we enter a post-scarcity era, and everyone gets a generous universal basic income (UBI). Assuming AGI is cheap, UBI is also cheap, and humanity lives happily ever after.

Risk #2: “AI may spread misinformation”

The policy space for solving this risk seems less well understood.

Some things are obvious. For example, the Future of Life open letter calls for watermarking systems to easily distinguish between human-generated and AI-generated content. That’s a low-hanging fruit, and we should require AI companies to do this.

Other things are more complicated. For example, should we have liability for AI-caused harm? Let’s say Joe asks ChatGPT for medical advice, the medical advice provided by ChatGPT is dangerously incorrect, and Joe suffers a stroke as a result. Should Joe be able to sue OpenAI? There should be some penalty when companies knowingly or negligently allow their AIs to do crazy things. However, such liability would probably hurt innovation.

What about “AI audits”? I’m unsure how they can work without, in effect, becoming “truth committees” where the government decides what’s true and what’s not, what’s biased and what’s not. Perhaps there are smart ways to do third-party audits or create industry standards that solve the problem without getting into Orwellian territory. That said, I’m all up for algorithmic transparency and accountability. Make sure the AI companies are as open as possible about what’s under the hood.

Lastly, distribution channels are key. If I create lots of misinformation with ChatGPT, but the only person who can see that misinformation is me, I have not inflicted much harm. Arvind Narayanan makes this point nicely when commenting on The Future of Life open letter, arguing that the critical bottleneck for misinformation is distribution:

That means social media platforms will have an important role to play here as well, not just AI developers.

Risk #3: “AI may destroy humanity”

That leaves us with the third—and most controversial—risk.

Here’s a simple decision tree I find helpful for thinking about the problem:

First, we must ask if we will get AGI (i.e., artificial general intelligence). If the answer is “no,” there’s nothing to worry about. Next, if we do get AGI, will it pose a significant threat to humanity? If the answer is “yes” to both of those questions, we should do something. Even then, however, we need to know what the practical options are.

Let’s put some probabilities on these questions. I’m a big fan of Metaculus, a forecasting platform, so let’s start there.

First, how likely is it that AGI will be developed? At the time of writing, Metaculus forecasters predicted AGI would arrive in 2032—less than a decade away! Honestly, I find this timeline too rapid. That’s mainly because the forecast attributes much of the timeline reduction to GPT-3.5 and GPT-4, and it’s unclear to me whether GPT technology will lead to AGI. Additionally, Metaculus attracts individuals enthusiastic (or concerned) about AGI, creating a selection effect. Therefore, I would consider 2032 to be a lower bound. For example, Samotsvety forecasting team, a group of superforecasters, gave a ~30% chance of AGI being developed in the next 20 years, and predicted a ~70% probability of AGI being developed by 2100 (forecasts made in mid-2022), which is more consistent with my personal view.3

Assuming AGI is developed within the predicted timeframe, what is the likelihood of human extinction? Here’s the closest question I could find on Metaculus: What’s the probability that the global population will decline by more than 95% due to AGI, conditional on AGI arriving between 2030–2039? The question has limited participation (only ~30 forecasters), but the median prediction is a depressing 30%. Similarly, the Samotsvety group gave a ~40% chance of existential catastrophe from AI, conditional on AGI being developed by 2070.

These probabilities are unsettlingly high. For example, if you assign a 50% probability to AGI within the next ~50 years and a ~30% probability to catastrophic risk conditional on that, there’s a 15% chance of an AGI catastrophe within the next couple of decades. Given such numbers, you could make a strong case that AI is a greater existential risk than nuclear weapons or climate change.

I want to emphasize that these forecasts are highly uncertain. For the first question (“when do we get AGI?”), we can at least ground the predictions on pretty objective data on the current state of AI. Define what you mean by AGI, evaluate where we currently are, assume how quickly we can improve, and extrapolate. That’s still tricky, as forecasts about future technology are famously inaccurate. (You know the joke that “nuclear fusion is always 30 years away.”) However, the second question (“how likely is an existential catastrophe conditional on AGI?”) is much more difficult. The reason is that we don’t have much to base our forecasts on. Humans have not yet been wiped out, but that does not mean your base rate for existential risk should be 0%. So, what should your base rate be? Scott Alexander summarized this conundrum nicely:

You can try to fish for something sort of like a base rate: “There have been a hundred major inventions since agriculture, and none of them killed humanity, so the base rate for major inventions killing everyone is about 0%”.

But I can counterargue: “There have been about a dozen times a sapient species has created a more intelligent successor species: australopithecus → homo habilis, homo habilis → homo erectus, etc - and in each case, the successor species has wiped out its predecessor. So the base rate for more intelligent successor species killing everyone is about 100%”.

Anyway, although uncertain, these forecasts provide us with some data points on expected AGI timelines and existential risk. However, a key question remains: If we’re on a path to AGI and face a high chance of catastrophe, what can we do about it?

Again, there’s a lot of disagreement. Some people are pretty optimistic about making sure that AGI aligns with human goals (“aligned AGI”). Others believe solving alignment is unlikely. (Currently, Metaculus forecasters assign a <10% chance that the alignment problem is solved before we create a “weak” AGI.)

Answering the “can we solve alignment?” question is crucial. If you believe the “alignment problem” is essentially intractable and AGI is imminent, the only logical option is to halt all AI development. If you think the “alignment problem” is solvable, the policy prescription is to invest heavily in safety research. Alignment research is a public good, and the private sector, on its own, will underinvest in it.

Lastly, remember the arms-race dynamic I mentioned earlier? Unfortunately, this dynamic applies to countries as well. For instance, if the US perceives rogue AGI as an existential risk and stops research into the subject, will China follow suit? I’m betting that the answer is “probably not.” With AGI's immense power, individual countries will have a tremendous incentive to win the AGI race. Once you win the race, you can just prompt the AI to “create a dark-energy annihilator to destroy my enemies” (or something like that). That prize may be too tempting to forgo.

In the end, international cooperation might be the answer. We could establish something similar to the International Atomic Energy Agency, but for AI. Working together to tackle AGI development and safety, countries could establish common standards and pool alignment research. However, securing and maintaining this cooperation is not easy. Plus, there’s the pesky fact that once trained, AI is mostly non-physical. AI systems can be copied, making oversight and control that much harder.

Where do I stand?

Where do I stand on this complex issue, personally?

As previously mentioned, I don’t have a strong stance or a very well-formed opinion. However, I do believe there are several fundamental, uncontroversial measures we ought to take quickly:

Watermark AI-generated content;

10x public investment in AI alignment and safety;

Establish clear transparency and safety guidelines.

But what about going beyond these steps?

Should we pause AI research, as The Future of Life Institute advocates? My intuition leans towards “no.” Considering the arms-race dynamic, a moratorium might even be counterproductive. Currently, the US maintains a healthy lead over other nations. If the US unilaterally ceases research, it would merely provide less trustworthy nation-states an opportunity to catch up. I'm writing this post from Europe, and unfortunately, Europe seems to lag years behind the United States in AI development, counterexamples such as AlephAlpha notwithstanding. Does the US want to become more like Europe in this respect? Instead of a moratorium, I would be much more in favor of accelerating common-sense safety regulations.

Also, we cannot discuss the risks of AI without discussing its benefits. I use ChatGPT every day, and I find it invaluable. Moreover, large language models haven’t even been properly integrated into our software. The potential benefits of these models for medicine, coding, and science are immense. The “precautionary principle” is valid, but so is “first, do no harm.”

Gosh, this was a long post. My hope is to have provided a map of the terrain. The map is blurry and unclear, and we have little idea of what’s on the horizon. Best of luck to us in traversing this territory.

My discussion is necessarily incomplete. For example, I will not cover data privacy and intellectual-property concerns.

A note on the payoffs: You can think of these numbers as representing profits from the different actions. Let's assume that if we reach AGI safely, total profits in the market equal 10. If both OpenAI and Google play “move slow,” assume that they each get a 50% market share, and therefore a payoff of 5. If one firm plays “move slow” while the other plays “move fast,” assume that the whole market (and all profits) are captured by the firm that plays “move fast.” That yields a payoff of 10 for the fast-moving firm and 0 for the slow-moving firm. If both firms "move fast," that increases existential risk and reduces the size of the total pie from 10 to 2 (which is then divided 50:50 between the two firms).

For another alternative perspective, we can consult this survey of AI researchers. In this survey, the prediction for a “50% chance of AGI” is 2059, nearly 30 years later than the current Metaculus forecast. (Yes, the questions are not directly comparable, and the AI researchers’ survey took place in mid-2022.)

I think that payoff matrix is a typo; it's set up for the Nash equilibria to be {slow, fast} and {fast, slow}.

The payoff structure as it is written as the "chicken game" (or other similar variants), instead of the prisoners dilemma.